van Emde Boas Trees

Published:

Introduction to vEB-tree and its implementation

Introduction

The van Emde Boas Tree (vEB-tree) is a search tree structure designed to manage a set of integer efficiently. Unlike traditional data structures like binary search trees or heaps, which rely on comparison model and operate in $O(\log{n})$ time, the vEB-tree leverages the natural of integer keys to achieve faster operations – specifically, $O(\log{\log{u}})$ time for updates and queries. Here $u$ represents the size of universe (the range of possible integer keys, from 0 to $u-1$), and $n$ is the number of elements stored.

Motivation

Imagine you need to maintain a dynamic subset $S$ of integers from a universe $U={0, 1, \dots, u-1}$, where $S\subseteq U, \lvert S\rvert=n, \lvert U\rvert=u$. Your goal is to perform operations like insert, delete, find an element, get successor, and get predecessor in $O(\log{\log{u}})$ time, using $O(u)$ space.

Here’s what these operations mean:

insert(x): Add $x\in U$ to $S$, i.e., $S\leftarrow S\cup{x}$.remove(x): Remove $x\in S$ from $S$, i.e., $S\leftarrow S-{x}$.find(x): Report whether $x\in S$.successor(x): Return the minimum $y\in S$, where $y\ge x$.predecessor(x): Return the maximum $y\in S$, where $y\le x$.

Let’s explore how we can approach this problem and evolve toward the vEB-tree.

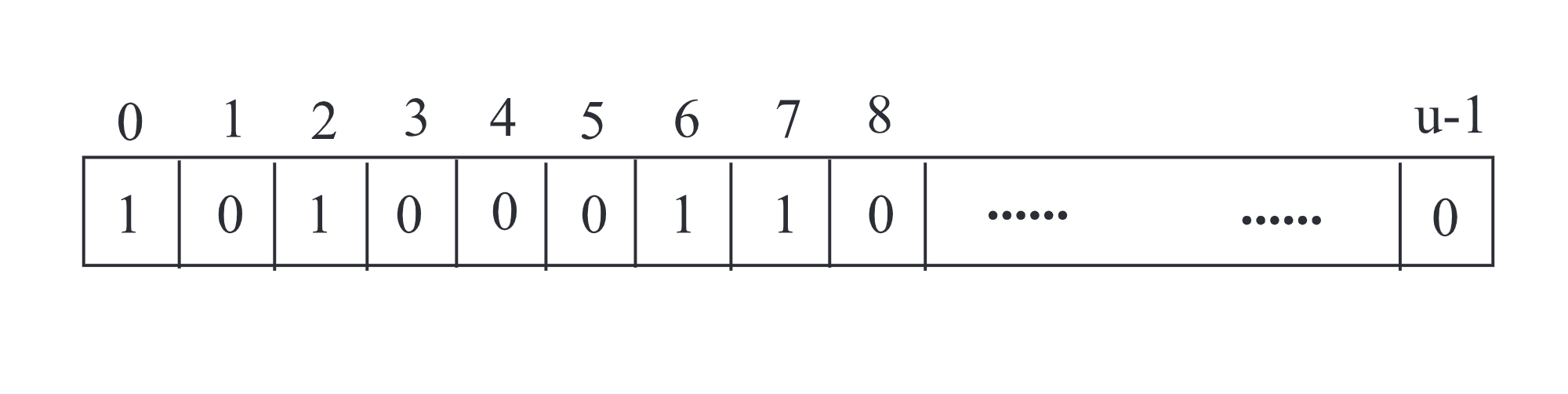

Starting point - a bit vector

A simple solution is to store elements in an array with size $u$. Each index $i$ corresponds to an integer in $U$. if a[i] = 1, then $i\in S$; otherwise, if a[i] = 0, $i\notin S$.

- Pros: Space is $\Theta(u)$, and insert and delete are $O(1)$, just flip a bit!

- Cons: Finding successor or predecessor requires scanning the array, taking $O(u)$ the worst-case time. That’s too slow…

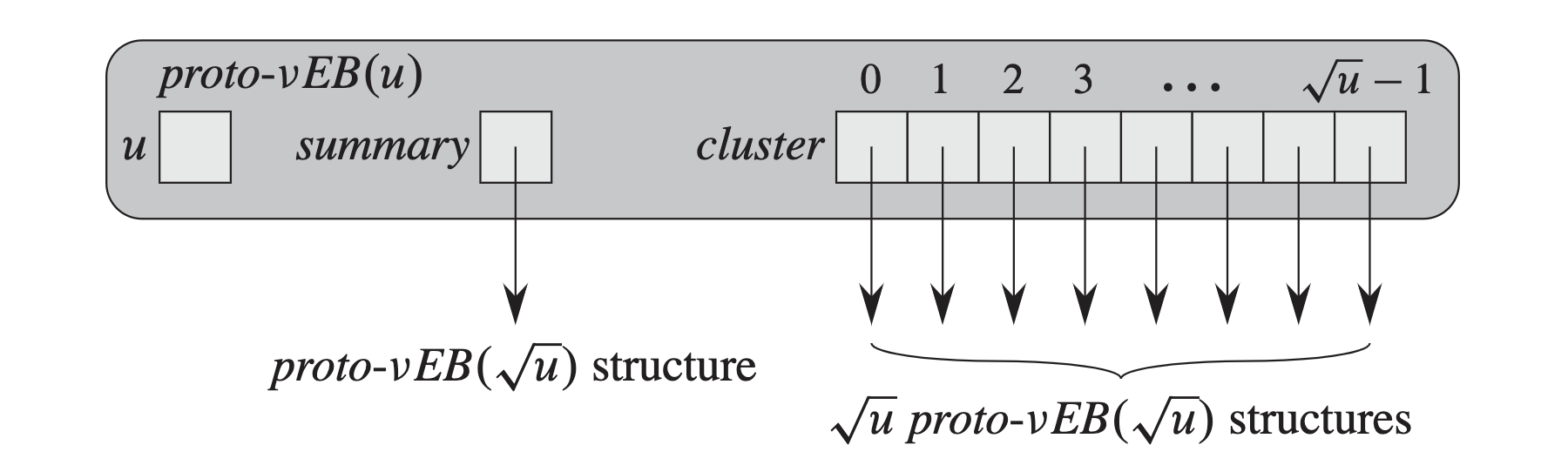

Next step - a tree with cluster and summary

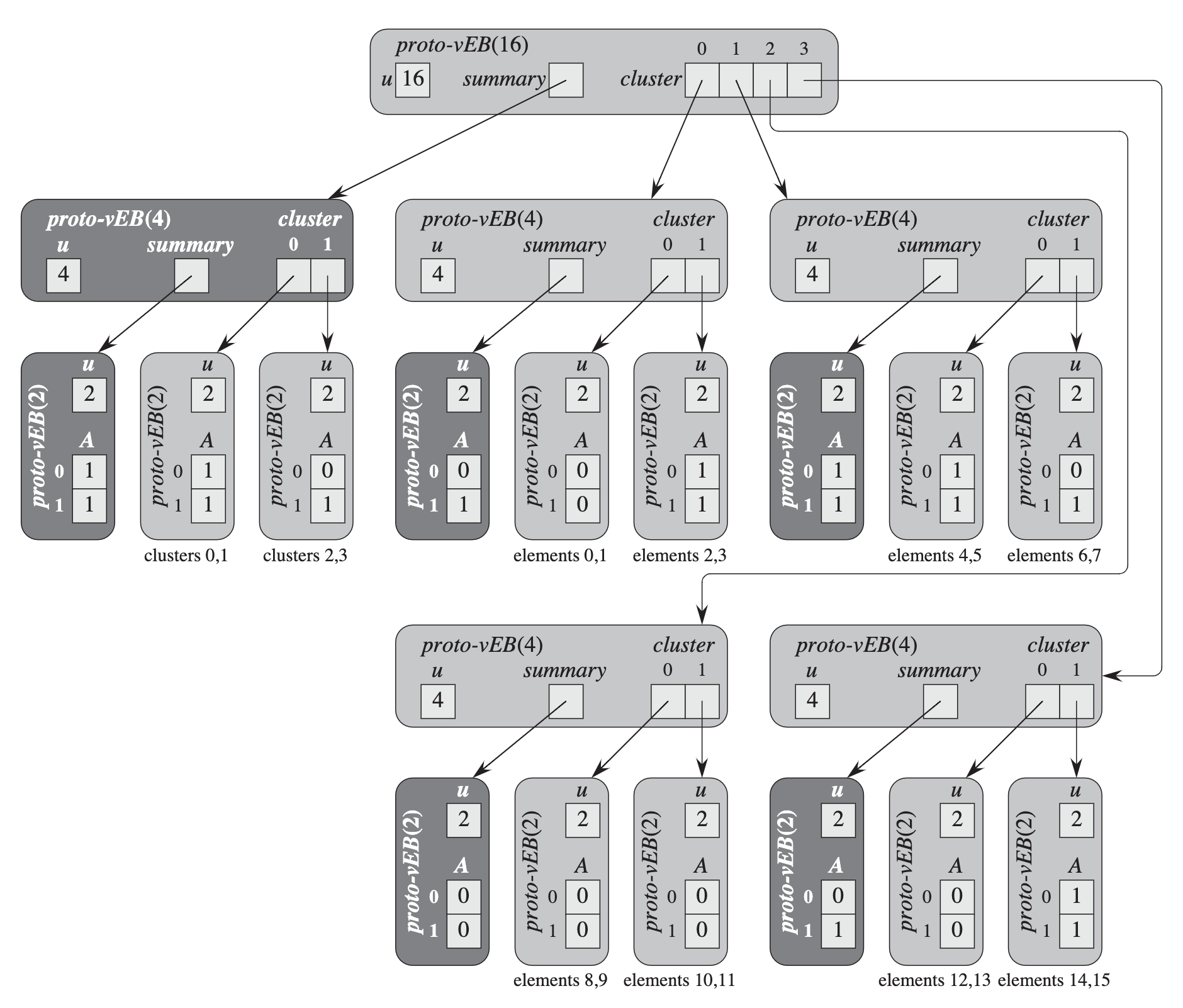

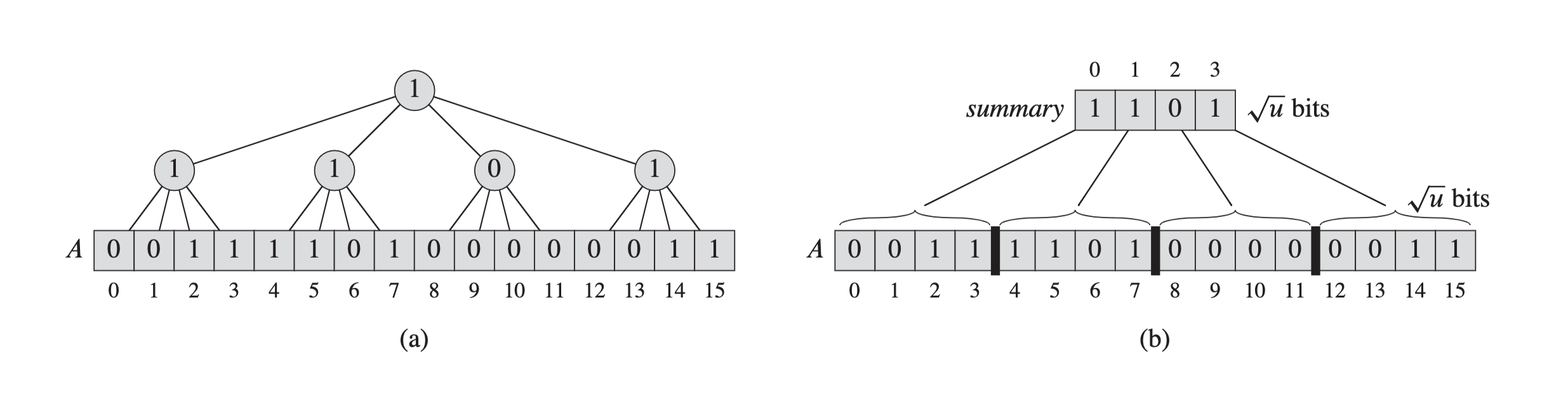

To speed up the scan through the bit vector, we can superimpose a tree structure on top of it. Picture the items of the bit vector as the leaves of the tree, with internal nodes summarizing their children using a logical OR operation (figure a). Therefore, the bit vector seems to be split into $\sqrt{u}$ clusters of size $\sqrt{u}$ bits, and the existing information of each cluster is managed by $\sqrt{u}$-bit summary (figure b).

- Space: Become $O(u)$.

- In each of insert, delete, successor, or predecessor operation, we need to search at most two clusters with $\sqrt{i}$ bits plus access the summary once. So each operation takes $O(\sqrt{u})$ time. Using a tree of degree $\sqrt{u}$ is a key idea of vEB-trees!

A recursive approach - divide and conquer

The vEB-tree takes this idea further with recursion. It works by repeatedly splitting the universe into smaller pieces, each of whose size is the square root of its parent’s size. This leads to a recurrence for the time complexity: $T(u)\le T(\sqrt{u})+O(1)$, which solves to $T(u)=O(\log{\log{u}})$.

Given universe size $u$, the randomized, full version of vEB-tree offers:

- $O(\log{\log{u}})$ worst-case time for insert, delete, find, successor, and predecessor queries.

- $\Theta(u)$ space to store the entire nodes.

vEB-tree

Notations

We always represent a vEB-tree and some of its operations in the following notations for simplify the description.

| Notation | Explanation |

|---|---|

| $U$ | the universe |

| $x$ | a $u$-bit integer within $U$ |

| $high(x)$ | high-bit of $x$, i.e., $\lfloor x/2^{\lceil u/2\rceil}\rfloor$ |

| $low(x)$ | low-bit of $x$, i.e., $x\mod 2^{\lceil u/2\rceil}$ |

| $concat(h, l)$ | concatenate the high-bit $h$ and the low-bit $l$ |

| $V$ | a vEB-tree (or a sub-tree) |

| $V.min$ | the minimum value in $V$ |

| $V.max$ | the maximum value in $V$ |

| $V.summary$ | the set of high-bits in $V$ |

| $V.cluster[h]$ | the subtree of $V$ with high-bit $h$ |

Construction

Each tree node $V$ has a consistent structure, defined in C++ as node_t. It includes min and max to record the minimum value and maximum value in the (sub-)tree, a summary, and a cluster array. When $V$ is empty, we set $V.min=V.max=NIL$. For the rest keys in $V$, their high-bits are maintained recursively in $V.summary$. For each unique high-bit, the relevant low-bit are also organized recursively in $V.cluster[h]$.

// 56B per node

template<typename T>

struct node_t {

size_t u;

std::optional<T> min_v;

std::optional<T> max_v;

std::unique_ptr<node_t<T>> summary;

std::vector<std::unique_ptr<node_t<T>>> cluster;

};

The code snippet is my original design of the node structure. Each node stores a universe size $u$, as well as an optional type of min and max value in a node. Both are initially set to std::nullopt, which seems to be more robust than just setting them to -1 when testing unsigned integers. However, every node with this implementation cost 56B, and to build a complete vEB-tree we will allocate $\Theta(u)$ nodes, the memory overhead is too much. This requires ~430 GB of memory to store and ~440 sec to construct the tree in experiments, which seems impractical. We could make it smaller and faster!

// 16B per node (for 32-bit int)

template<typename T>

struct node_t {

T min_v;

T max_v;

std::unique_ptr<node_t<T>[]> A;

};

Why this design?

- Decouple the subtree size $u$ by recursive passing instead storing in every node, as it is predictable.

- Replace the optional type to the original type. Compared to use optional type, using

-1as a flag for invalid status eases type checking, frees up memory bottlenecks, and speedup execution. - Combine

summarywithclusterreduce the extra container overhead. It put the summary at the back of the cluster array, which can be access byA[sqrt(u)], which is as simple as before. - Use shift operation instead of calculate square root to get size $u$. This is because bitwise shift (integer) operations are more efficient than floating-point arithmetic.

In this case, the node sizes drops from 56B to 16B. In practice, it only demands ~116G memory and ~120 sec time to build (3.7x smaller and faster). What a fantastic optimization!

Split & Concat

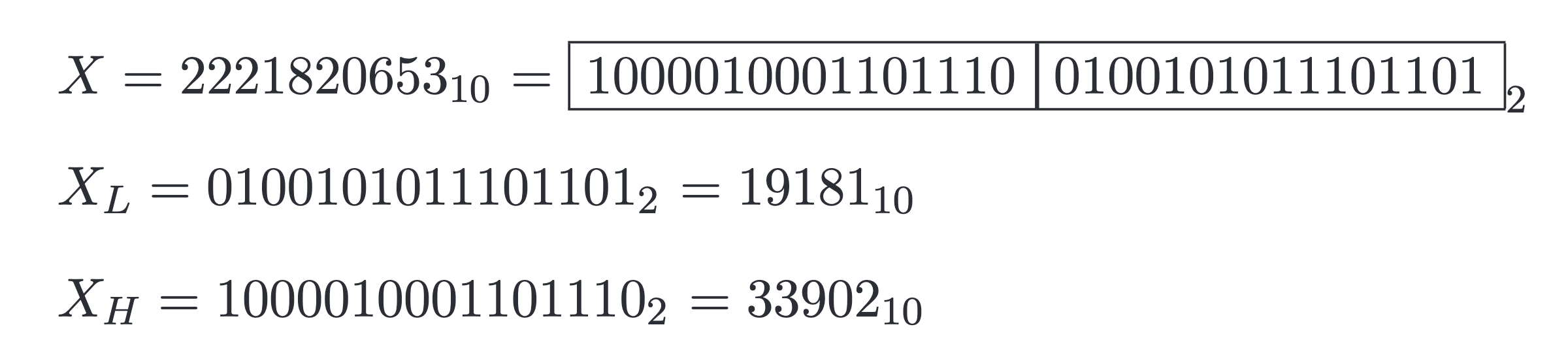

vEB-trees store a $u$-bit integer by breaking the number into high-bits (upper half of the bits or the first $u/2$ bits) and low-bits (lower half bits). The operation to split a 32-bit integer to get its high-bits and low-bits is represented as the following figure:

To get the high-bits and low-bits of an integer $x$ (with $u$ bits) in constant time, they can be calculated as:

$high(x)=\lceil x/\sqrt{u}\rceil$

$low(x)=x\mod \sqrt{u}$

The concat operation reverses this process, combining the high and low bit parts: $concat(h,l)=h\cdot \sqrt{u}+l$.

inline std::pair<T, T> _split(T v, size_t s) const {

T high = static_cast<T>(v / (1ULL << s));

T low = v % static_cast<T>(1ULL << s);

return std::make_pair(high, low);

}

inline T _concat(T high, T low, size_t s) const {

return high * static_cast<T>(1ULL << s) + low;

}

Insert & Find

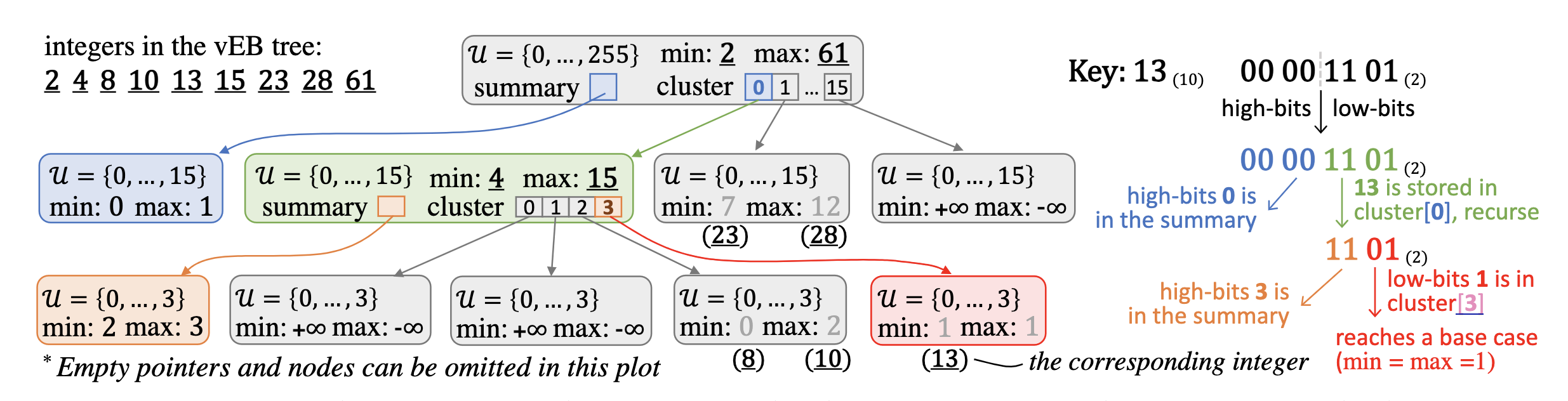

Here is an example to insert a 13 to a vEB-tree with $u=2^8$.

To insert the key $13$ into a vEB-tree with a universe size $u=2^8$, the process starts at the root, where the key $13(00001101)_2$ is split into high-bits $0(0000)_2$ and low-bits $13(1101)_2$, based on $\sqrt{u}=16$. The value $0$ is recursively stored in $V.summary$, and we recurse into $V.cluster[0]$, a subtree with $u=2^4$ to store $13$. There, key $13(1101)_2$ is split into high-bits $3(11)_2$ and low-bits $1(01)_2$. $3$ goes into the summary, and we move to $V.cluster[3]$ with $u=2^2$. This time, key $1(01)_2$ splits into high-bits $0$ and low-bits $1$, storing $0$ in the summary. At the base case, $1$ is directly stored in $V.cluster[0]$ and then return.

Here is the details of insertion:

template<typename T>

void vEBTree<T>::insert(node_t<T> &node, T x, size_t s) {

// lazy (every item except V.min will be recursively inserted)

if (node.min_v == NIL) {

node.min_v = node.max_v = x;

return;

}

if (x < node.min_v) std::swap(node.min_v, x);

if (x > node.max_v) node.max_v = x;

if (s <= 1) return;

auto [high, low] = _split(x, s / 2);

if (node.A[high].min_v == NIL) {

insert(node.A[1ULL << (s / 2)], high, s / 2);

}

insert(node.A[high], low, s / 2);

}

In a vEB-tree, the insert method adds a value $x$ into a node with a universe size $u=2^s$, where $s$ denotes the number of bits shifted. The process begins by checking if the node is empty (i.e., $V.min=V.max=NIL$). If so, it simply assigns $x$ to both $V.min$ and $V.max$ and terminates. This lazy propagation efficiently handles the insertion of the first element in a constant time without recursion. When the node already contains values, it compares $x$ with $V.min$ and swaps two values if $x$ is smaller, ensuring that $V.min$ always holds the smallest value non-recursively in the tree. Following this, it updates $V.max$ if $x$ is greater, and exits if it reaches the base case ($u=2$). For $u>2$, it gets high-bits - $high(x)$ and low-bits - $low(x)$ of $x$ based on a split at $s/2$. The high-bits determine which cluster $x$ belongs to, while the low-bits specify its position within the cluster. If $V.summary$ is empty ($V.summary.min=NIL$), insert $high(x)$ to the summary. Subsequently, recursively insert $low(x)$ into $V.cluster[high(x)]$. Although an insertion might involve two recursive calls, insert to an empty summary will only assign the $V.min$ and return happen in $O(1)$ time. It thus ensure the efficient $O(\log{\log{u}})$ insert time.

The find method in a vEB-tree provides a simpler yet similar approach to determining whether a value $x$ exists within the structure. Here is the code of finding:

template<typename T>

bool vEBTree<T>::find(const node_t<T> &node, T x, size_t s) const {

if (x == node.min_v || x == node.max_v) return true;

if (s <= 1) return false;

auto [high, low] = _split(x, s / 2);

if (node.A[high].min_v == NIL) return false;

return find(node.A[high], low, s / 2);

}

Successor & Predecessor

template<typename T>

T vEBTree<T>::successor(const node_t<T> &node, T x, size_t s) const {

// lazy (V.min is not stored recursively)

if (x < node.min_v) return node.min_v;

if (s <= 1) {

if (x == 0 && node.max_v == 1) {

return 1;

}

return NIL;

}

auto [high, low] = _split(x, s / 2);

if (low < node.A[high].max_v) {

low = successor(node.A[high], low, s / 2);

if (low != NIL) return _concat(high, low, s / 2);

}

high = successor(node.A[1ULL << (s / 2)], high, s / 2);

if (high == NIL) return NIL; // larger than the last

low = node.A[high].min_v;

return _concat(high, low, s / 2);

}

For the successor method, we focus on getting the upper bound for value $x$. It can be easily convert to the lower bound by finding the successor of $x-1$. The algorithm first checks if $x$ is less than the minimum value stored in the current node; if so, returns $V.min$ as the successor, which is a trivial operation. In the base case where $u=2$, the only valid successor occurs when $x=0$ and $V.max=1$. For $u>2$, the algorithm splits $x$ as it previous does. If the low-bits of $x$ is less than the maximum value in the cluster, the successor lies within the same cluster, and the algorithm makes a recursive call to find it. Otherwise, if the low-bits are not less or if the cluster is empty, the algorithm search the $V.summary$ recursively to locate the next non-empty cluster with a higher index. Once such a cluster is found, it combines the high-bits with the minimum value from that cluster to form the successor. Although it may seem that the process involves two recursive calls, typically either one recursion is executed. Since the low-bits and $V.max$ are compared in constant time, it ensures that the overall operation takes in $O(\log{\log{u}})$ time.

Getting the predecessor is similar to getting the successor. Here is the detailed code snippet:

template<typename T>

T vEBTree<T>::predecessor(const node_t<T> &node, T x, size_t s) const {

if (node.max_v != NIL && x > node.max_v) return node.max_v;

if (s <= 1) {

if (x == 1 && node.min_v == 0) {

return 0;

}

return NIL;

}

auto [high, low] = _split(x, s / 2);

if (node.A[high].min_v != NIL && low > node.A[high].min_v) {

low = predecessor(node.A[high], low, s / 2);

if (low != NIL) return _concat(high, low, s / 2);

}

high = predecessor(node.A[1ULL << (s / 2)], high, s / 2);

if (high == NIL) return NIL;

low = node.A[high].max_v;

return _concat(high, low, s / 2);

}

Remove

template<typename T>

void vEBTree<T>::remove(node_t<T> &node, T x, size_t s) {

if (node.max_v == node.min_v) {

// only the last node

node.min_v = node.max_v = NIL;

return;

}

// base case (0 + 1 only)

if (s <= 1) {

node.max_v = node.min_v = (x == 0 ? 1 : 0);

return;

}

// if x is V.min (check if it's the last node in the cluster)

if (x == node.min_v) {

// get the first cluster id

T next = node.A[1ULL << (s / 2)].min_v;

if (next == NIL) {

node.min_v = node.max_v;

return;

}

// not last node

// delete old & update V.min

// remove new V.min from recursive storage

x = node.min_v = _concat(next, node.A[next].min_v, s / 2);

}

// recursively delete

auto [high, low] = _split(x, s / 2);

remove(node.A[high], low, s / 2);

// delete summary if it's the last one

if (node.A[high].min_v == NIL) {

remove(node.A[1ULL << (s / 2)], high, s / 2);

}

// if x is V.max (update V.max)

if (x == node.max_v) {

// get the last cluster id

T last = node.A[1ULL << (s / 2)].max_v;

if (last == NIL) {

// delete the second last item (only one item left)

node.max_v = node.min_v;

} else {

// find the last item in the cluster

node.max_v = _concat(last, node.A[last].max_v, s / 2);

}

}

}

The remove method deletes a key $x$ from the vEB-tree, assuming that the key is stored in the tree. First, if the node contains only one key (i.e., $V.min=V.max$), that key is stored non-recursively, so both $V.min$ and $V.max$ are simply set to $NIL$ to empty the tree. If the tree has two or more keys, the base case occurs when the universe $u=2$, the node holds exact two keys, $0$ and $1$, and deleting $x$ means replacing it with the other key by updating both $V.min$ and $V.max$. Then we are doing something similar to lazy propagation when $x=V.min$. The algorithm finds the smallest cluster using $next=V.summary.min$, get the second smallest value $V.cluster[next].min$ if it’s not $NIL$, update the $V.min$ using this key, and remove it recursively from the tree. After the deletion, if the $V.min$ of the cluster becomes $NIL$, it updates the summary by removing the empty cluster to completely eliminate the key. Finally, if the key $x$ is the maximum in the tree, the algorithm checks $V.summary.max$ to locate the last non-empty cluster, retrieves its maximum key, and update the $V.max$ accordingly. The time complexity of remove operation is $O(\log{\log{u}})$.

Evaluation

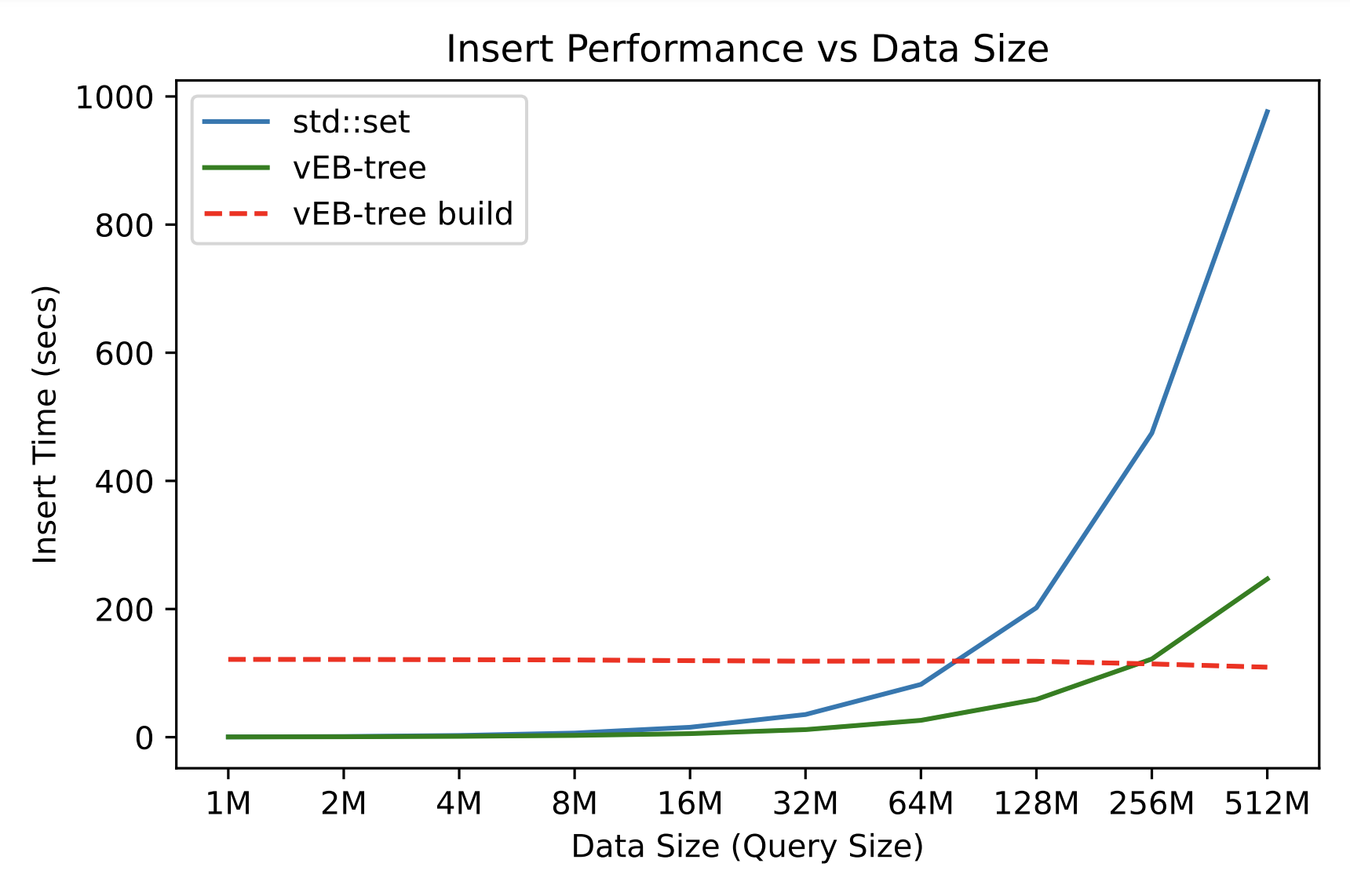

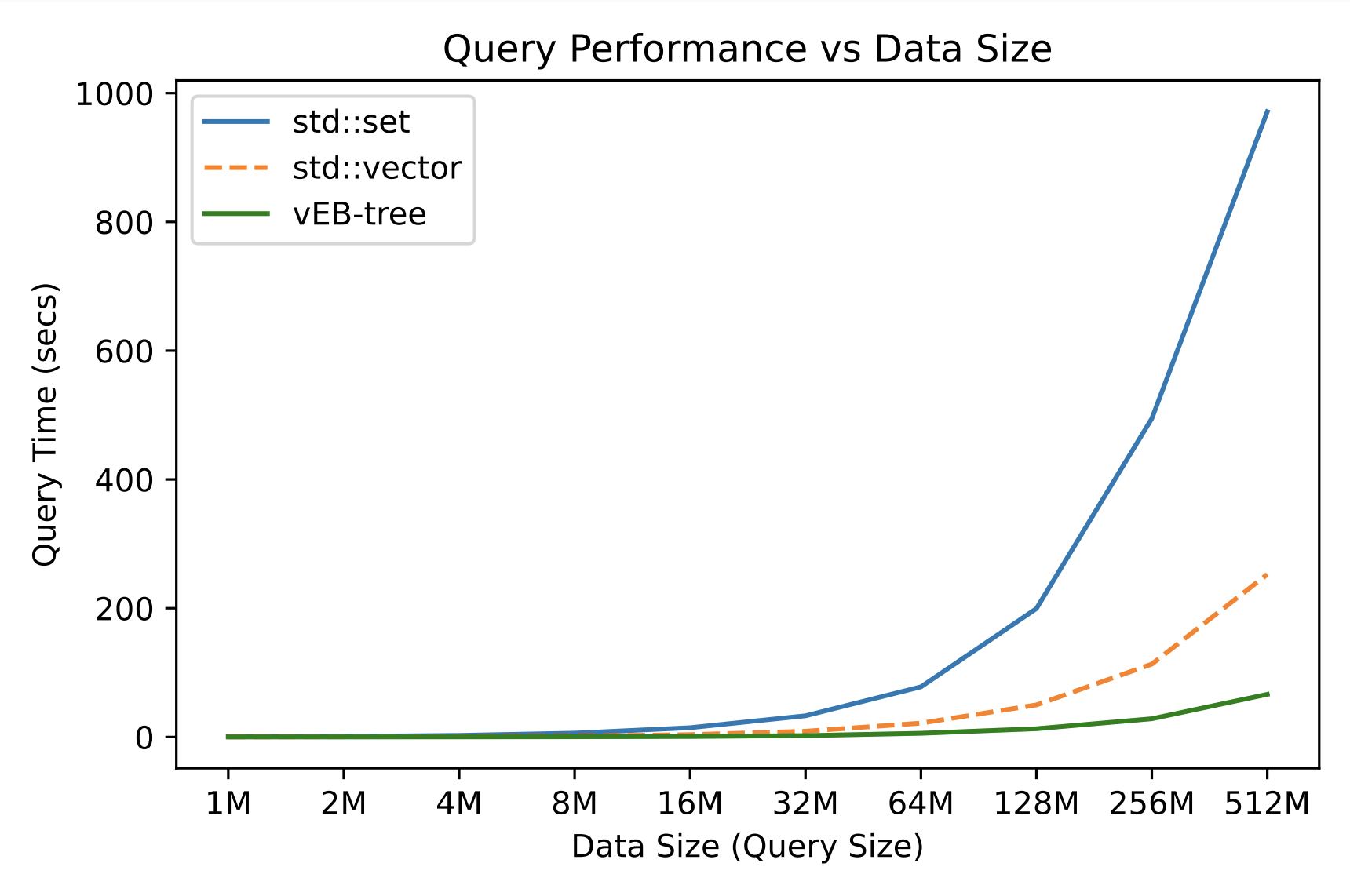

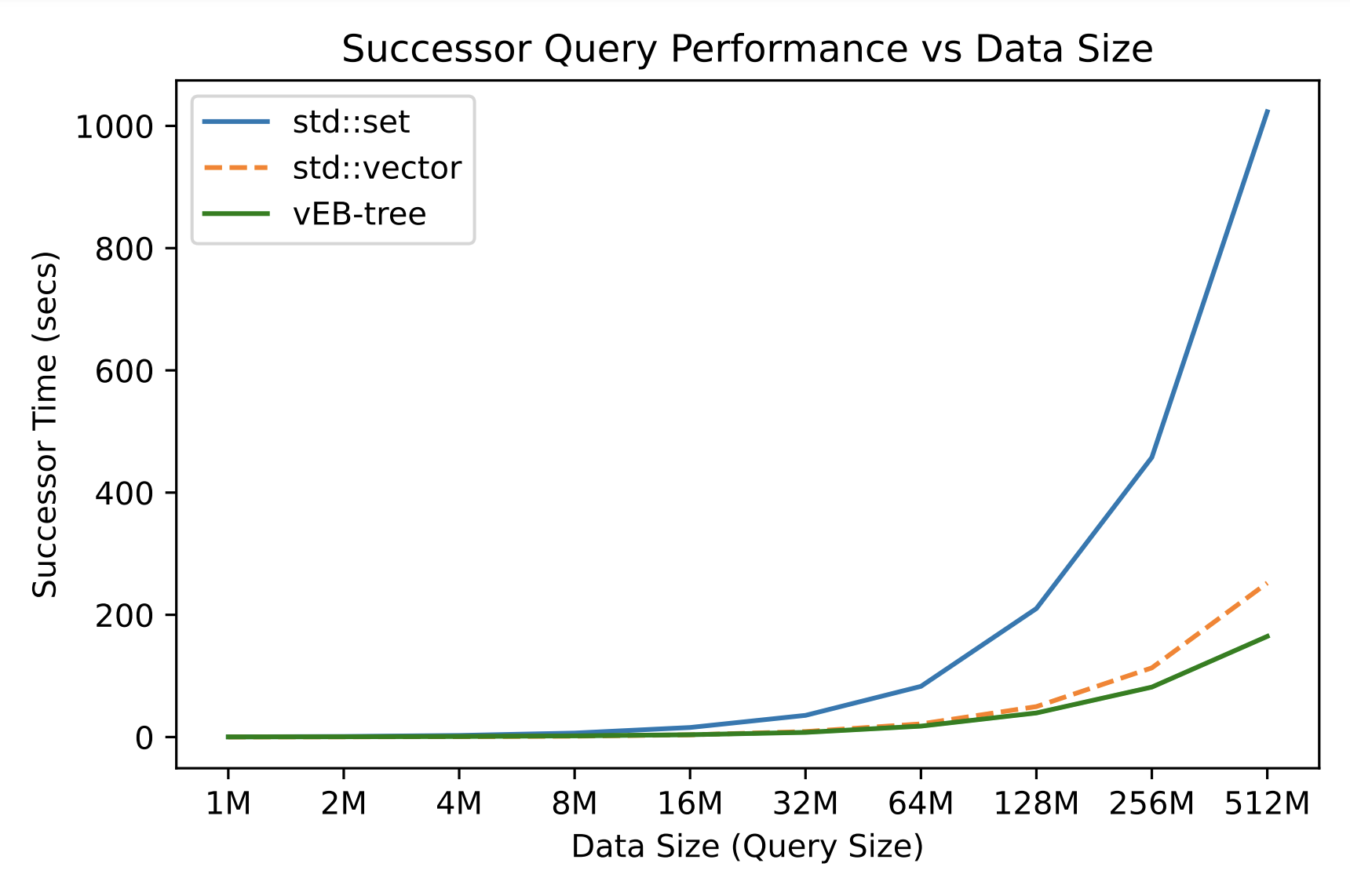

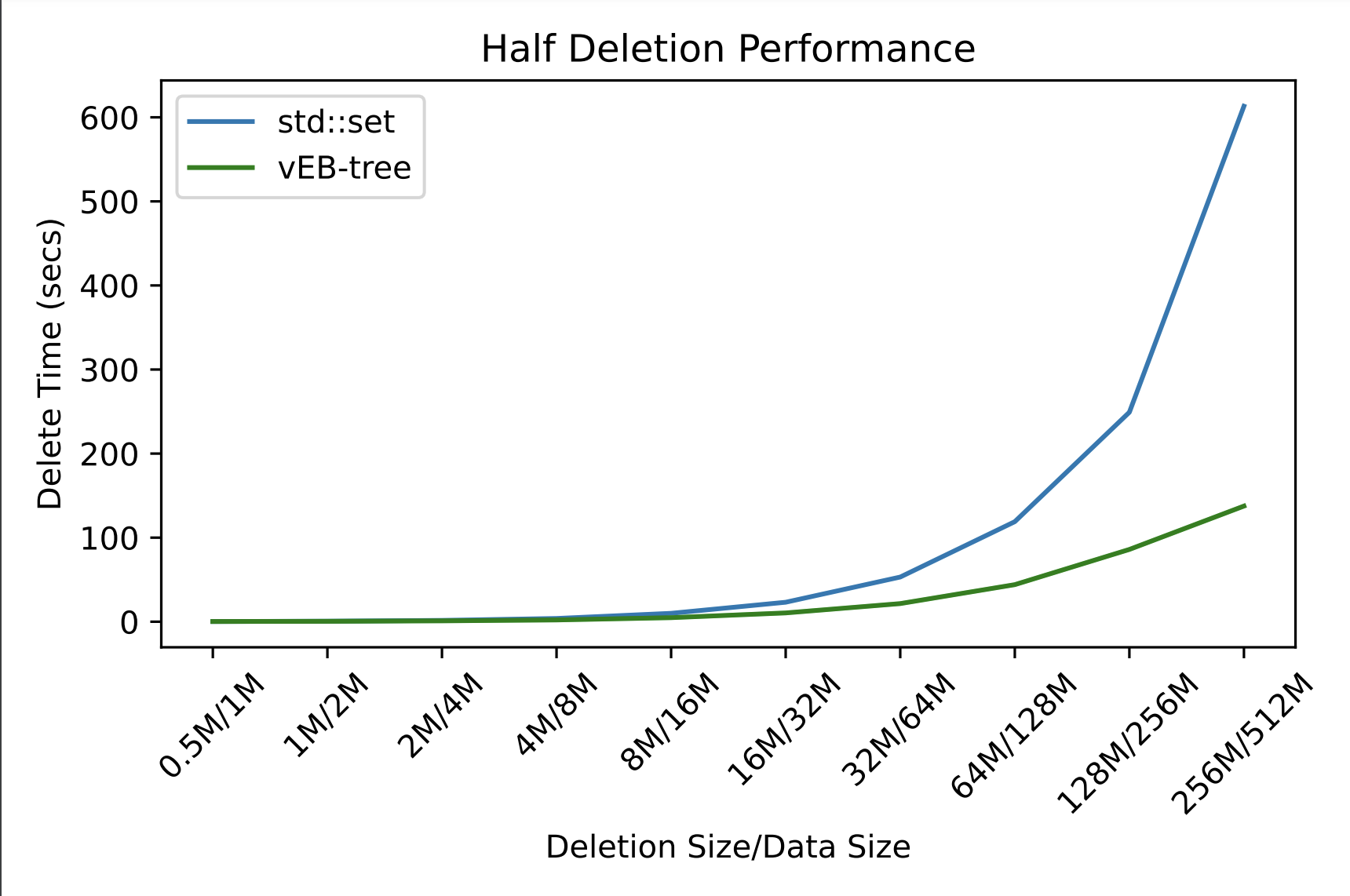

In the evaluation, I compared the performance of insert (including construction), query, successor, and delete operations among three data structures – std::set (red-black trees), std::vector (binary search as the lower bound of logarithmic operations), and our vEB-tree. The query size (data size), represented as powers of 2, ranged from 1M to 512M queries. Experiments indicated that the vEB-tree provides little advantage over std::set in smaller data, but its construction time introduces significant overhead. However, as the number of queries increases, especially when the data exceeds 64M, the performance of operations in the vEB-tree surpasses the std::set. In such cases, the constant construction time of the vEB-tree becomes negligible relative to the overall performance boost on large data. We do not compare the insertion and deletion of sequential model std::vector because push_back operations is trivial, and deletions in it takes $O(n)$ time, which are meaningless.

The figure shows the performance of vEB-tree and std::set for insertion, with a notable red line indicating the constant build time of vEB-tree.

The figure shows the performance of vEB-tree, std::set, and std::vector for query. In std::vector, it calculates the run time of lower_bound excluding the time of std::sort, which reveals the bound of logarithmic operations.

This figure shows the performance of vEB-tree, std::set, and std::vector for finding successor. It also applies and calculates the runtime of lower_bound in std::vector.

This figure compares the performance of vEB-tree and std::set for deletion.

References

[1] van Emde Boas, Peter. “Preserving order in a forest in less than logarithmic time.” In 16th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (sfcs 1975), pp. 75-84. IEEE, 1975.

[2] Cormen, Thomas H., Charles E. Leiserson, Ronald L. Rivest, and Clifford Stein. Introduction to algorithms. MIT press, 2022.

[3] Yan Gu, Ziyang Men, Zheqi Shen, Yihan Sun, and Zijin Wan. “Parallel Longest Increasing Subsequence and van Emde Boas Trees.” In Proceedings of the 35th ACM Symposium on Parallelism in Algorithms and Architectures, pp. 327-340. 2023.

[4] Willard, Dan E. “Log-logarithmic worst-case range queries are possible in space Θ(N).” Information Processing Letters 17, no. 2 (1983): 81-84.

[5] Prashant Pandey, “CS 7280/4973 – Data Str & Alg Scalable Comp” Khoury College of Computer Sciences, Northeastern University, https://www.khoury.northeastern.edu/home/pandey/courses/cs7280/spring25/schedule.html.

Code can be found at https://github.com/sujingbo0217/vEB-tree.